Who Funded This Forest?

How one tree gets planted three times — and still apparently looks good on a dashboard.

We hear a lot about 'double counting" in reforestation and other climate solutions. But rarely do we hear why it happens, or how.

Counting trees should be easy. Tree gets planted. Tree gets tallied. Boom. Done. Simple.

But in the world of climate finance, even something as straightforward as planting a tree gets wrapped in layers of corporate-speak: blended finance, additionality, corresponding adjustments. Blah blah blah. What does it all mean?

The actual work of tree-planting happens on the ground but the claims flow upward into ESG/CSR reports, where sometimes many actors take credit for the same forest.

It sounds complicated, but we have a few simple words for it: misrepresentation. Double counting. Greenwashing.

A government fund backs a project. A corporate ESG donation chips in to help. A nonprofit implements the thing. And then: three sets of claims for one set of trees, with no ultimate reconciliation.

This may sometimes be a spreadsheet error, but when done knowingly, it's fraud. The math isn't hard, but the narrative scaffolding built around it — the buzzwords, the branding and the fancy dashboards — often tell a story de-coupled from the real data.

Collaboration or Creative Accounting?

You’ve probably seen the term “blended finance” in a glossy ESG report, sandwiched between some tree photos and a carbon-neutral promise. It sounds cooperative, even virtuous. But behind the buzzword, what are we actually blending?

Blended finance is a strategy that combines public, private, and philanthropic funds to support environmental projects — like large-scale tree planting — that no single actor is willing or able to fund alone.

This model is now powering much of climate finance. Like all quiet engines, it works best when you don’t ask too many questions. It’s fast, flexible, and designed for scale — the financial equivalent of a group project where everyone chips in just enough to keep things moving.

Who could oppose epic climate-solution team-ups? Certainly not us — but let’s not confuse group work with everyone turning in the same essay.

Blended finance doesn’t cause double counting — but it makes it easier to get away with. When multiple financiers support the tree project and then each writes it up in their own sustainability report, the result isn’t always synergy — it’s often statistical déjà vu. The trees may be real. But if everyone takes full credit for the same stand, the math gets fuzzy fast.

And in an era where climate progress is measured in targets, metrics, and dashboards, that kind of fuzzy math can quietly distort the story — inflating impact, eroding trust, and turning even well-intentioned reforestation into a forest of ghost claims.

This Shouldn’t Be Complicated

Nature-based solutions — including reforestation, mangrove restoration, and agroforestry — are chronically underfunded. According to UNEP, 82% of current NbS financing globally comes from public sources, with domestic governments providing over $120 billion annually. The private sector had only mobilized 17% of current financing. And this annual tally needs to double, fast.

Blended finance emerged as a workaround: a way to pool resources from public, private, and philanthropic sources that, on their own, wouldn’t be enough to fund a full-scale project. No single actor covers the whole bill — but together, they make it work.

Several recent initiatives offer insight into how this works. The Livelihoods Carbon Fund III, for instance, blends grants and guarantees to support agroforestry and ecosystem restoration projects, with the goal of sequestering 30 million tonnes of CO₂ while improving smallholder livelihoods. It received early-stage support from the Global Environment Facility and risk protection from the U.S. Development Finance Corporation — a structure designed to draw in commercial investors.

Other examples include Café Selva Norte in Peru, which helps coffee farmers rehabilitate degraded plantations and adopt sustainable practices, generating 3.8 million tonnes of CO₂ credits. And Terra Global Capital’s funds support reforestation and forest conservation in emerging markets, pairing technical assistance with carbon finance to boost project credibility and community impact.

But while the financial plumbing gets increasingly sophisticated, one critical layer still leaks: attribution.

And when attribution leaks, accountability does too. Projects get billed more than once. Impact is claimed multiple times. In some cases, that’s merely confusion. In others, the reporting crosses the line into fraud — especially when multiple claims are knowingly stacked.

How Many Trees Are We Planting, Exactly?

Enough to fill the press releases, apparently.

The Tree Planted Twice

There is increasingly widespread awareness of double counting in climate solutions (or triple counting, or multiple attribution with high narrative compression, depending on your epistemological tolerance). Nature-based solutions are no exception here.

In a 2024 article from DeSmog, experts flagged that tree-planting activities funded by Shell in the Netherlands may be counted twice — once by Shell and once by the Dutch government toward its national climate targets. “There is no way of separating out individual tree planting projects,” said campaigner Rachel Perlman, “so to sell them when there is a high likelihood that these activities go to fulfilling the regulation is a likely double counting.”

An article from Green Planet phrases it more bluntly: “This is when multiple parties claim they planted the same trees, creating an inflated perception of how many trees are really getting planted globally.”

And then there’s the broader structural layer. In 2014, the Stockholm Environment Institute mapped out four forms of double counting in climate solutions:

- Double issuance, where two sets of credits are issued for the same reduction

- Double claiming, where two actors count the same results

- Double use, where a credit is used more than once

- Double purpose, where one action is counted toward both emissions and finance pledges

At scale, this isn’t a rare failure mode — it’s a likely outcome of distributed ambition and silo-ed reporting. Veritree’s Derrick Emsley has noted that the system behind nature-based solutions is messy by design, and that reports of large-scale fraud — whether deliberate or accidental — are now a weekly occurrence. In other words: it’s a structure that actively enables double counting.

This isn’t necessarily classic greenwashing. But it is what LessWrong might call a coordination failure with high narrative compression.

Patchwork Fixes for a Global Problem

Some organizations have recognized the attribution problem and are trying to address it — but the landscape is uneven. In the voluntary carbon market, registries like Verra and Gold Standard now require tools like nested accounting and corresponding adjustments to avoid double claiming between countries and private buyers. It’s still perceived as far from perfect, but at least it’s a system.

In contrast, the broader world of charity-funded or ESG-branded reforestation still operates without shared identifiers, centralized registries, or consistent rules about who gets to claim what.

This doesn’t make ESG planting invalid. In many contexts, it's the only source of reforestation finance. But it does create fertile ground for “ghost claims” — outcomes that look meaningful in isolation, but multiply suspiciously when you try to tally global progress.

One Tree Planted avoids attribution overlap by refusing co-funding relationships where credit boundaries can’t be clearly drawn. They back this with geotagged imagery, site visits, and detailed partner agreements that prevent duplication. The trees are fully accounted for.

EcoMatcher takes a notably granular approach to transparency. The platform assigns GPS coordinates to individual trees, provides photographic evidence of planting, and includes basic information about the people doing the work. Some of the planting maps on its site are overly broad or imprecise, but the more detailed “Forest Tracker” tool does show specific geotagged points for each tree. While it’s unclear how scalable this model is for large-scale reforestation, the effort to document trees at the individual level represents a technical attempt to solve a broader problem: the lack of reliable, shared attribution infrastructure in ESG-focused planting efforts.

These are steps in the right direction. But they’re also siloed. None of these platforms are interoperable with national carbon registries, international finance tracking systems, or other restoration platforms like Restor.Eco, Carbon Offsets Map or Tree-Nation.

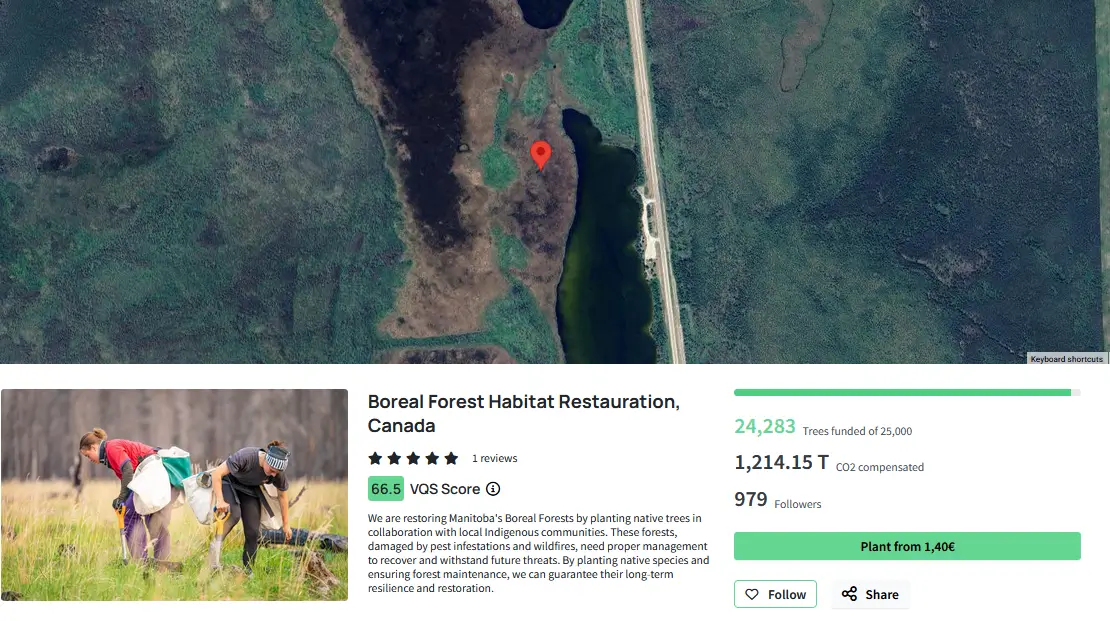

For instance, try cross-referencing project pages from Tree-Nation with records from Canada’s 2BT program, and it becomes immediately unclear whether you’re looking at duplicate claims or just parallel projects by the same proponents in similar regions.

Are these the same project?

Even if the data exists, turning it into verifiable, auditable claims isn’t cheap. Public-facing Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) is the backbone of accountability in forest projects, but traditional MRV systems remain expensive and time-intensive. According to a 2022 1t.org report, MRV costs can range from $0.15 to $1.40 per ton of CO₂, with smaller projects paying more due to fixed overheads. That’s often enough to make participation financially infeasible for small landowners or grassroots initiatives. Without scalable, low-cost alternatives, even technically sound solutions can struggle to reach the forest floor.

Why This Isn’t Just a Spreadsheet Problem

Reforestation is rooted in soil, but the accountability layer is increasingly digital — and increasingly fragmented. Right now, tracking impact often feels like solving a crossword with several missing clues, some of which were written in a different language, and others which have since been deleted in a PDF from 2017.

The consequences are not trivial. In the short term, double counting leads to inflated impact metrics, undermining trust in ESG claims and public programs alike. In the long term, it risks turning nature-based solutions into what economists call “credence goods” — things that are widely praised but poorly understood, which often leads to their being undervalued, misused, or eventually abandoned.

The risks aren’t just theoretical. Large-scale reforestation programs have already shown how hard it is to track real progress.

Ethiopia’s Green Legacy Initiative, for example, has drawn praise for its ambitious 50-billion-tree target. But critics have raised concerns about inconsistent reporting, survival rates, and the feasibility of planting that many trees across varied landscapes. Without robust data or verifiable tracking, it becomes hard to tell whether we’re celebrating real progress — or just adding zeros to a spreadsheet.

If nature-based climate finance collapses under its own ambiguity, it won’t be because the trees failed. It’ll be because the spreadsheets never agreed on where they went.

Blended Beverages and Singular Claims

It’s not just a measurement problem. It’s a market failure.

In reforestation today, you can execute the best project in the world and get very little for it. Or you can contribute essentially nothing and collect top-dollar — because what you’re really selling isn’t outcomes, it’s claims. And those claims can be duplicated, resold, repackaged, and marketed again under different logos.

That’s not simply "creative accounting". It’s what Canadian treeplanters would call "overclaim". And when it’s done knowingly, it’s fraud — no matter how many sustainability buzzwords are printed on a report.

What resolves this isn’t more branding. It’s transparency.

Reforestation should be the easiest sector to clean up. Trees don’t move. Projects are geolocated. Data is cheap. There is no technological barrier to shared registries or clear attribution — just a financial incentive to avoid them.

But that’s changing. As climate finance matures, transparent forests — the ones with traceable funding, verifiable outcomes, and a single claim per tree — will become more valuable than glossy, untraceable pledges. The market is catching on.

It’s not complicated. If one drink shows up on three bar tabs, someone’s getting overcharged. It doesn’t matter how it was mixed — it’s still the same cocktail.

If each of three funders pays 40% of the cost, the result is not 120% of a forest. It’s one tree and three very confident PDFs.

Sources

American Forests, 1t.org US, & World Economic Forum. (2022, April). Technology and MRV in forest carbon finance. 1t.org.

BE Ultimate. (2024, April 22). Veritree X BE Ultimate: Planting trees to make an impact. BE Sustainable.

Carbon Market Watch. (2025, March). Overview of the carbon removals and carbon farming certification process.

Cooke, P. (2020, July 6). Investigation: The problem with big oil’s ‘forest fever’. DeSmog.

Halton, C. (2021, April 13). Credence good: Meaning, issues and examples. Investopedia.

López-Vallejo, M. (2021). Non-additionality, overestimation of supply, and double counting in offset programs: Insight for the Mexican carbon market. In Towards an emissions trading system in Mexico: Rationale, design and connections with the global climate agenda (pp. 191–221).

Malloy, V. (2022, February 24). This brand wants to help you offset your not-so sustainable daily pleasures. Coveteur.

Mior, S. (2025, February 5). Do tree planting promises measure up? – Sri Lanka edition. Ground Truth Forest News.

Mior, S. (2025, February 18). Ethiopia’s 50 billion tree plan: Hype or reality?. Ground Truth Forest News.

Morfo. (2024, November 9). Financing carbon credits for forest restoration projects: Separating fact from fiction. Morfo.

Pullella, E. (2024, November 19). Legitimizing carbon markets: The role of blended finance. Convergence Blog.

Schneider, L., Kollmuss, A., & Lazarus, M. (2014). Addressing the risk of double counting emission reductions under the UNFCCC. Stockholm Environment Institute, Working Paper No. 2014-02.

United Nations RSS. (2022, August 11). Can you really plant and grow a tree for one dollar? We break it down. Journalwide.

Van de Voorde, A., Elms Garcia, C. M., Chowdary Yetukuru, R. L., & Binyameen Noor, S. M. (2023, March). Incorporating nature into finance: Scaling up nature-based solutions. Knowledge Report, LSE x ASI.

Edited by Chris Harris

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.