Is Net Zero Set to Crush Indigenous Land Rights?

A billion hectares for climate pledges by 2060. The catch? Much of that land belongs to Indigenous peoples with insecure rights.

When “Net Zero” Sounds Less Like Climate Progress and More Like Land Trouble

We all want to save the planet. But some climate solutions, particularly land-based carbon offsets, seemingly carry serious trade-offs. A new report from TMG Research and the Robert Bosch Stiftung, Net Zero & Land Rights, warns that the global push for land-based carbon offsetting could trigger a new wave of land grabs. And no, this isn't theoretical.

Behind the soothing language of “net zero” and “natural climate solutions” lies a blunt reality: Indigenous Peoples and local communities are at growing risk of being displaced from lands they’ve stewarded for generations — in the name of carbon removal.

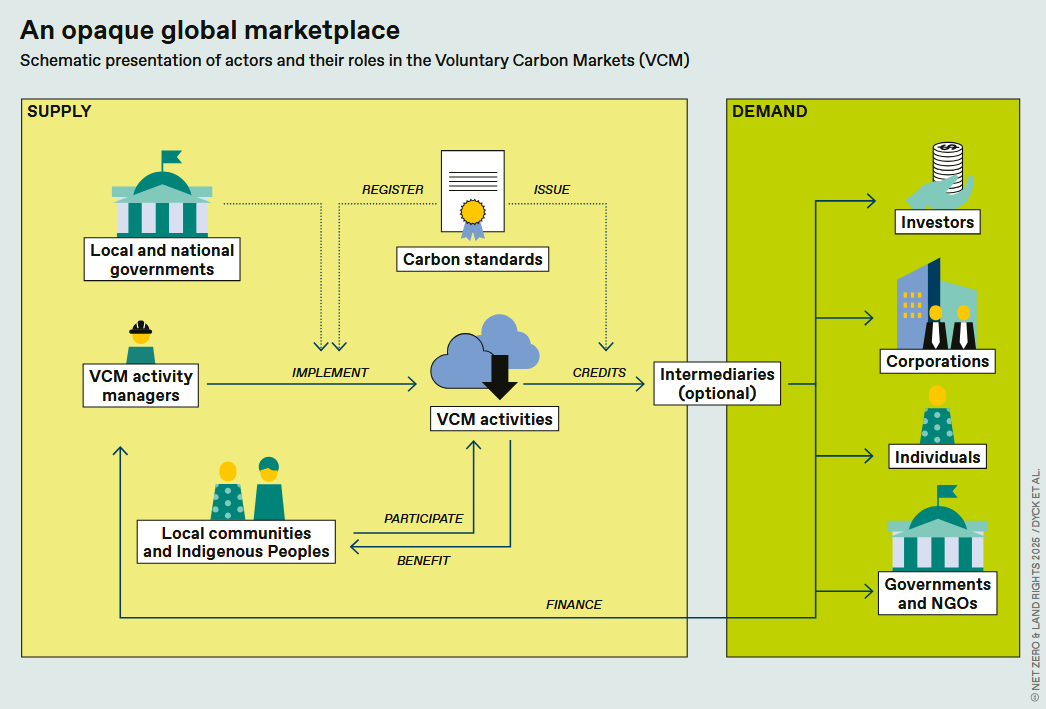

Behind the Carbon Market Boom: What’s Really Being Sold

To meet national climate pledges by 2060, countries will need access to up to one billion hectares of land — roughly the size of China. The report makes clear that much of this land is already occupied, cultivated, or protected by Indigenous and local communities.

But when land is seen primarily as a “carbon sink,” not as home, there is a risk that the people who live there get treated like a footnote. Or worse: an obstacle to be removed.

The Great Net Zero Mirage

Let’s be blunt: some climate pledges are not just overly optimistic — they’re mathematically impossible. Global climate commitments frequently underestimate competing land-use demands, ignoring the realities of food production, biodiversity, and human life. Look at Ethiopia's tree -planting pledges, for example.

And instead of reducing emissions at the source (ahem, fossil fuels), wealthy nations and companies are buying their way to carbon neutrality in countries with weak land rights and limited legal protections.

Carbon offset projects now cover tens of millions of hectares. And yes, some do involve communities and offer benefits. But others? Displacement, dispossession, and promises that don’t pan out.

Gender Gaps and Ghost Contracts

The report is especially sharp on gender: carbon market deals often recognize only male heads of household, leaving women — who are often the primary users of the land — out of the loop and out of the benefits.

In practice, that means many communities are losing their land not through bulldozers, via opaque contracting processes they were never consulted on.

Africa’s Role And Risks

Africa's ecosystems absorb an astonishing amount of CO₂ — and that's made the continent ground zero for land-based carbon schemes. But with most land held under customary tenure, and formal recognition still patchy, it's the perfect storm for exploitation.

The report documents projects that restrict grazing lands, trigger displacement, or simply never deliver the promised benefits to local people.

The Myth of “Empty Land”

One of the most dangerous assumptions underpinning these projects? The idea that land is “unused” if it’s not fenced, farmed, or mapped in a Western bureaucratic sense.

In places like the Congo Basin the land may lack formal titles, but it’s anything but empty. It’s deeply inhabited, managed, and culturally significant. When that gets ignored, many ambitious reforestation plans start looking less like climate action and more like erasure.

Can’t We Just… Check Online?

You’re probably thinking: “Surely we can just look up where these carbon projects are and cross-check them with maps of Indigenous land rights, right?”

Well that’s the neat part. In many instances, we can't.

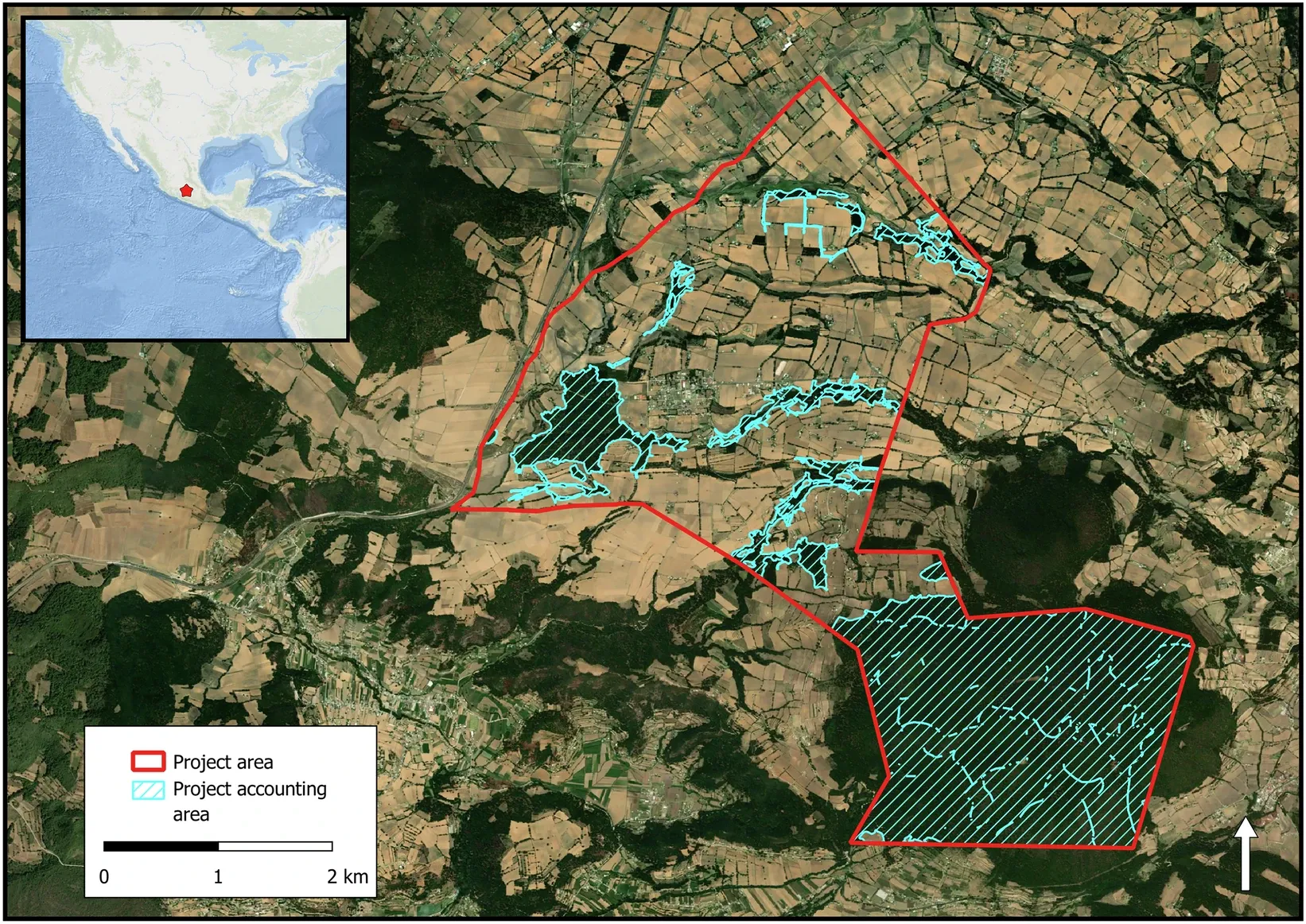

Verra, the biggest name in voluntary carbon markets, requires projects to define their boundaries. But as of this year, over 25% of Verra projects don’t publish any official boundary data at all. And among those that do? Some are wildly inaccurate — including one project that “accidentally” mapped parts of the ocean (check out this hilarious analysis of one Canadian initiative from Carbon Plan).

So no, you can’t reliably check whether a carbon offset overlaps with Indigenous land. Transparency, it turns out, is kind of optional.

What If We Actually Had Maps That Worked?

Here's the thing: the technology does exist. We have satellites, open-access platforms, and project registries. But the current mapping landscape is a mess — fragmented, incomplete, and often wrong.

A universal map (or at least, many open, shareable and interoperable maps) of carbon offset projects, backed by verified data and open access, wouldn’t fix every injustice. But it would make it harder for projects to operate in the shadows. And it could give communities a powerful tool to assert their rights — or at least see what’s happening around them.

Global Land Alliance’s verdict is blunt: weak land governance, opaque carbon deals, and scarce boundary data in the VCM create an information asymmetry that fuels land grabs and undermines FPIC. Their fix points straight at mapping: build a global, open geodatabase of planned and existing carbon projects so communities can spot overlaps with their territories and hold developers to account.

What the Report Actually Recommends

(Spoiler: It’s Not Just “Plant More Trees”)

The authors don’t just diagnose the problem — they propose a serious rethink. Here's what they say needs to change:

- Recognize and protect land rights, including customary and communal tenure systems.

- Center communities in decision-making, including the right to say no.

- Close the gender gap in land access and benefit-sharing.

- Create real grievance mechanisms — not just a suggestion box.

- Integrate human rights into carbon market regulations, globally and nationally.

- Slow down and regulate before the carbon offset market becomes a land free-for-all.

The Last Word: Maps, Markets, and the Power of Being Seen

The report’s message is simple: if land-based climate solutions come at the expense of land rights, they’re not solutions — they’re just repackaged problems.

Legal reform, stronger governance, and inclusive planning are non-negotiable. But so is visibility. Public-facing, reliable maps of where carbon projects actually exist could be a starting point — a way to challenge false claims, document violations, and make the system just a little harder to game. Without accurate, publicly available maps and supporting data, the public cannot meaningfully audit these projects — and accountability becomes impossible.

In a climate economy where trees are valued but the people who live beside them are not, transparency might be the first step toward real justice.

Sources

Eklund, G. R., Childress, M., & Barnes, G. (2023, October 9). Securing Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities’ land rights in the voluntary carbon market: Key considerations and actions [Policy brief]. Global Land Alliance

Karnik, A., Kilbride, J. B., Goodbody, T. R. H., Taubert, F., Ballhorn, U., Roe, S., & Herold, M. (2025). An open-access database of nature-based carbon offset project boundaries. Scientific Data, 12, Article 581

Lang, C. (2025, August 5). A “green rush” for carbon offsets is fuelling land grabs in the Global South. REDD-Monitor

Mior, S. (2025, February 18). Ethiopia’s 50 billion tree plan: Hype or reality? Ground Truth.

Mior, S. (2025, August 24). Who funded this forest? Ground Truth.

TMG Research, & Robert Bosch Stiftung. (2025, May). Net zero & land rights: How our climate goals drive land demand and shape people’s lives.

Edited by Chris Harris

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.