The Forest That Proves It: How Sudbury Reclaimed a Moonscape

A Canadian city brought new life to a damaged landscape—one tree, one polygon at a time—backed by openly available data.

How Sudbury Turned Open Data Into Civic-Scale Ecological Recovery

For much of the 20th century, the landscape of Greater Sudbury, Ontario, was a byword for environmental ruin. Decades of nickel and copper smelting released more than 100 million tonnes of sulfur dioxide annually, creating acid rain that annihilated soils, stripped forests, and left behind a barren, rocky expanse visible from space. NASA called it “moonscape material” and they weren’t exaggerating—astronauts trained there because the terrain resembled the surface of the moon.

Today, Sudbury is home to one of the world’s most transparently documented reforestation projects—an effort that didn’t simply green a moonscape, but also contributed to a model for ecological recovery backed by open knowledge.

The transformation didn’t happen overnight. It took years of experimentation, public coordination—and enough lime to shift the soil pH and restart ecological processes.

This is a brief overview of the Regreening Sudbury Project. Since the late 1970s, this initiative has turned scorched land into green space using soil amendments, careful mapping, and over 10 million planted trees—an effort refined over decades of fieldwork and fine-grained data collection. It’s a kind of slow-motion terraforming—less a grand gesture than a decades-long coordination between landscape ecologists, data managers, and municipal staff.

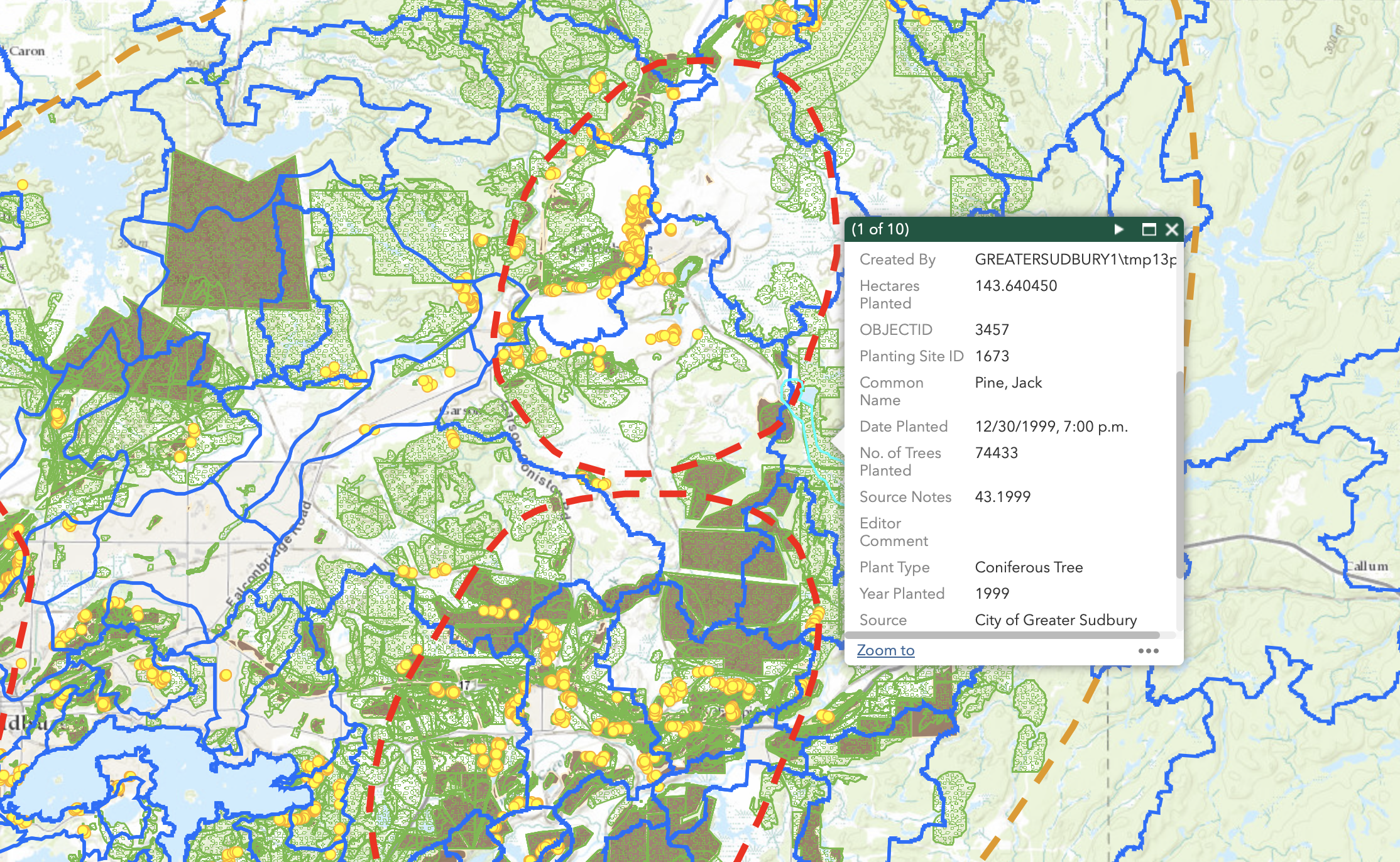

And crucially, for the data nerds among us, there's now a publicly available GIS app that lets you explore every lime-sprinkled hill and pine-planted plot since 1978. Want to know if that trail you jog is part of a decades-old ecological intervention? There’s a layer for that.

The Vegetation Technical Advisory Committee (VETAC), a long-running expert group, guides restoration strategy, land access, and species selection.

In the interview ahead, we dig into the roots (sorry, had to) of the project with VETAC—the team that’s been in the thick of it. From digital mapping to on-the-ground planting, Greater Sudbury’s transformation effectively showcases the practical impact of long-term science and data transparency.

Why Build an App to Track a Forest?

When Greater Sudbury started healing its scorched landscape back in the late ’70s, data collection was—let’s say—analog. “We used to do everything with pen and ink,” recalls Tina McCaffrey, the city’s Supervisor of Land Reclamation, who joined the regreening team in the early ’90s.

By 1999, GIS technology had entered the picture, but it was still years before digital maps became public.

Fast-forward to 2015: Sudbury adopts an open data policy, and suddenly the inboxes at VETAC are flooded with requests. Professors, students, casual forest enthusiasts—you name it, they wanted the data.

“We realized most of the emails were basically asking the same thing,” McCaffrey says. “So why not make it public?”

Krista Carre, Manager of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Operations for the City of Greater Sudbury, adds, “There was already a lot of demand. It just made sense.” That led to the development of a public-facing GIS tool that lets anyone explore where and how Sudbury’s landscape has been restored.

Certainly, not everyone got on board with the idea. “Some private landowners don’t love seeing reforestation maps showing up on their properties,” says David Grieve, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analyst and longtime VETAC member.

But that’s the minority. Grieve believes public support is strong, based on community feedback he’s seen over the years. “Interview the public,” he says, “and I guarantee they’d give it a 100% thumbs-up.”

More Than a Pretty Map

The app isn’t just for show—it’s an internal workhorse. “We use it constantly,” McCaffrey says. Whether it’s grant applications (“It proves we are legit,” she adds) or planning new planting zones, the map has become an essential tool.

Carre nods. “Visually, it helps everyone understand the scope. It’s really changed how we talk about the project.”

What sets it apart is its granularity. Users can search by species, planting year, number of trees, and even see the precise polygon shape and area of each site. Want to know how many jack pines were planted in 1980, and where? It’s there. Want to filter for deciduous trees planted on former smelter slag beds between 1979 and 1982? Go for it.

This level of public, long-term ecological data is almost unheard of in municipal infrastructure. Greater Sudbury’s platform doesn’t just show where trees were planted—it reveals how, when, and what was planted, block by block, year by year. That kind of visibility makes the project accountable and adaptable, giving researchers, city planners, and community members a shared frame of reference.

By contrast, most publicly available reforestation records in Ontario are far more fragmented. While it's possible to still find individual PDF reports from various Forest Management Units, there’s no centralized, publicly accessible system that shows where and what was planted (though there is a Wooded Areas map that estimates plantation areas).

Looking beyond harvest-cycle plantations, many ESG-driven tree planting projects around the world still don’t share spatial data in a usable or verifiable form. Without maps, observers are left guessing—unable to trace what was planted, where, or whether it endured. The same holds true for many projects in carbon markets.

Sudbury’s GIS platform on the other hand openly displays decades of planting activity, broken down by species, year, and geometry. It’s a rare example of ecological transparency implemented not just for experts, but for everyone. The kind of visibility that lets others trace, question, and reuse the work — not merely admire it.

It’s the same idea championed by platforms like explorer.land, Restor, or Open Forest Protocol: transparency isn’t a risk to be managed, or a secret only for experts to see—it’s the backbone of long-term credibility. The messy middle is where trust happens.

By visualizing historical planting patterns, the platform also helped identify under-served zones, assess survival trends, and prioritize new planting sites with more ecological resilience.

Polygons: proof that even in a reforestation project, there’s always at least one problem that exists solely to make GIS analysts sigh audibly.

Lessons for the Rest of the World

So what can other restoration projects learn from Sudbury’s open-data approach?

McCaffrey points out, “Sure, some places might hesitate—maybe they're worried about survival rates or land development. But you just have to go with it.” Biodiversity, by nature, is messy. “Some trees die, others thrive. We’re aiming for complexity, not perfection.”

It’s essentially the biodiversity equivalent of release early, release often. The point isn’t perfection—it’s iteration, feedback, and slowly converging on a landscape that works.

Those efforts haven’t gone unnoticed: the United Nations has recognized Sudbury’s efforts, and the late Dr. Jane Goodall herself helped plant the city’s 10 millionth tree. There’s even a documentary, Planting Hope, chronicling Sudbury’s journey from lunar wasteland to a recognized case of ecological recovery.

Trees are critical to the fight against #climatechange and the health of our communities. Today, PM @JustinTrudeau, Dr. Jane Goodall and I took part in a tree planting ceremony in Sudbury.

— Steven Guilbeault (@s_guilbeault) July 7, 2022

Any day I get to plant a tree is a good day in my books. 🌳 🐿 pic.twitter.com/69SRzOAVa3

The impact is measurable, and the numbers tell a story:

- 98% reduction in industrial air pollution

- 50% recovery of lost sport fish populations

- 3+ million tonnes of carbon sequestered

- Delisting of the aurora trout (a once-endangered species)

- 22% of the damage zone now converted to parks and reserves

Researchers at Laurentian University call it one of the world’s most successful urban ecological rehabilitations. The “Sudbury Recipe” is now actively studied and exported to other restoration efforts worldwide. It has been studied in mining reclamation zones from Cape Breton to Quebec and cited in global urban sustainability forums.

Partners, Challenges, and Planet-Sized Goals

VETAC’s work has been supported by a wide network of collaborators. Tree Canada contributed funding and seedlings during key expansion phases. Clothing brand tentree backed local planting blitzes around the 10-million-tree milestone. Mining companies like Vale and Glencore—whose operations today encompass mines once operated by Inco Ltd. and Falconbridge Ltd.—later became partners in site access and liming.

Laurentian University researchers continue to analyze biodiversity outcomes and monitor species survivability. Even arts groups like the Sudbury Earth Dancers have helped keep the effort rooted in community visibility.

Each partner brings something different to the table: funding, labour, land access, or public visibility. The long arc of the Regreening Program has depended on this kind of flexible, evolving collaboration—especially as priorities shifted from roadside planting to full-scale ecosystem recovery.

But the challenges have shifted, too. The project now operates under the growing pressure of climate change, which affects everything from tree survivability to planning logistics. Reforestation sites are increasingly located in more remote, fragmented parts of the region—areas harder to access, more expensive to monitor, and more vulnerable to drought, heat stress, and invasive pests.

“We started on the roadsides, just trying to make the city look less like a moonscape,” McCaffrey says. “Now the remote sites are harder to reach, and survival is less predictable.”

Also on their radar: water. “We have over 330 lakes,” McCaffrey notes. “Restoring land helps protect those water systems—it’s all connected.” The team now looks at reforestation as a way to stabilize shorelines, reduce runoff, and support aquatic ecosystems—especially in the face of increased storm variability and warmer temperatures.

The Open-Data Forest Builders

Greater Sudbury has developed what is likely one of the most granular, long-term reforestation databases maintained by a municipality in Canada. In a field where environmental data is often fragmented, paywalled, or buried in obscure PDFs, the platform made decades of planting records searchable by species, date, and location. It’s the kind of open and interoperable infrastructure the record-keepers, the mappers, the linkers — have been asking for all along.

It’s the same principle Alexander Watson of explorer.land described in a recent interview with Ground Truth: “Transparency is a universal moral duty. It’s the foundation for truth and trust.” Whether it’s Sudbury’s polygons or satellite-timestamped biodiversity updates in Peru, the idea is the same—open data is not boring. It’s how trust scales.

Sudbury’s polygons might look like bland cartography, but they tell a story many reforestation projects can’t (or won't): where the trees went, when they were planted, what species, and how much it cost to bring life back to poisoned land. It’s not flashy, but it’s real. And it’s open.

In a field where most reforestation data still lives in PDF purgatory or buried in institutional silos, Greater Sudbury’s platform sets a rare precedent: full ecological transparency at city scale.

In a warming world, where “restoration” is becoming the go-to buzzword for everything from carbon credits to ESG reports, what actually counts is what you can prove. And in Greater Sudbury, the proof is in the polygons. For open knowledge advocates, Sudbury’s platform proves that transparency can be a feature of the system, not a patch on it. The data doesn’t just support restoration—it is part of the process itself.

Sources

City of Greater Sudbury. (2015). Open Data Policy for the City of Greater Sudbury. City of Greater Sudbury.

City of Greater Sudbury. VETAC – Regreening Advisory Panel. City of Greater Sudbury.

Gemmill, A. (2022, July 7). 10 millionth tree in Sudbury, Ont., planted with Jane Goodall pitching in. CBC News.

Karnik, A., Kilbride, J. B., Goodbody, T. R. H., Ross, R., & Ayrey, E. (2025). An open-access database of nature-based carbon offset project boundaries. Scientific Data, 12(581). Nature Portfolio.

Laurentian University. (2022). Global lessons from the restoration story of Sudbury, Canada. Office of Sustainability, Laurentian University.

Laurentian University. (2022, December 21). Laurentian students and professor share Sudbury’s re-greening story at COP15. Laurentian University News.

Mior, S. (2024, November 20). Interview: Alexander Watson of OpenForests’ explorer.land. Ground Truth.

Monet, S., & McCaffrey, T. (n.d.). Regreening the moonscape: Greater Sudbury’s remarkable ecosystem restoration. Ontario Association of Landscape Architects (OALA) – Ground, Issue 56.

Phinney, W. C. (2015). Science training history of the Apollo astronauts. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA Special Publication 626).

Potvin, R. R., & Negusanti, J. J. (1995). Declining industrial emissions, improving air quality, and reduced damage to vegetation. In J. M. Gunn (Ed.), Restoration and recovery of an industrial region (pp. 51–65). Springer.

Special to The Sudbury Star. (2025, April 18). Sudbury’s earthdancers say climate crisis as urgent as ever. The Sudbury Star.

Edited by Chris Harris

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.