Second Trump Administration Threatens USDA Conservation and Insurance Programs

Family farmers fear the Conservation Reserve Program, a steady source of income, could be eliminated.

This story was originally published by Barn Raiser.

In the mid 1980s, Thomas Eich’s grandparents, who farmed corn and soybeans, enrolled in the newly established Conservation Reserve Program, administered via the U.S. Department of Agriculture to incentivize farmers to cease farming on environmentally sensitive land. His grandfather signed up for the program to help restore farmland on his 200 acre farm near the edge of the Kankakee River, which runs through their property.

The river is prone to flooding, which made yielding fruitful crops near the river a challenge, and the program incentivized them to swap out some farmland for a natural habitat.

Today, the 60 acres of CRP land on Eich’s grandparents’ property is fully in nature’s hands. Trees hug the shaded riverbank and large bushes provide a protective buffer between the river and active farmland. The land requires little maintenance and bears little evidence that it was once used as farmland. In addition to the environmental benefits, the land gives Eich’s grandfather a place to hunt.

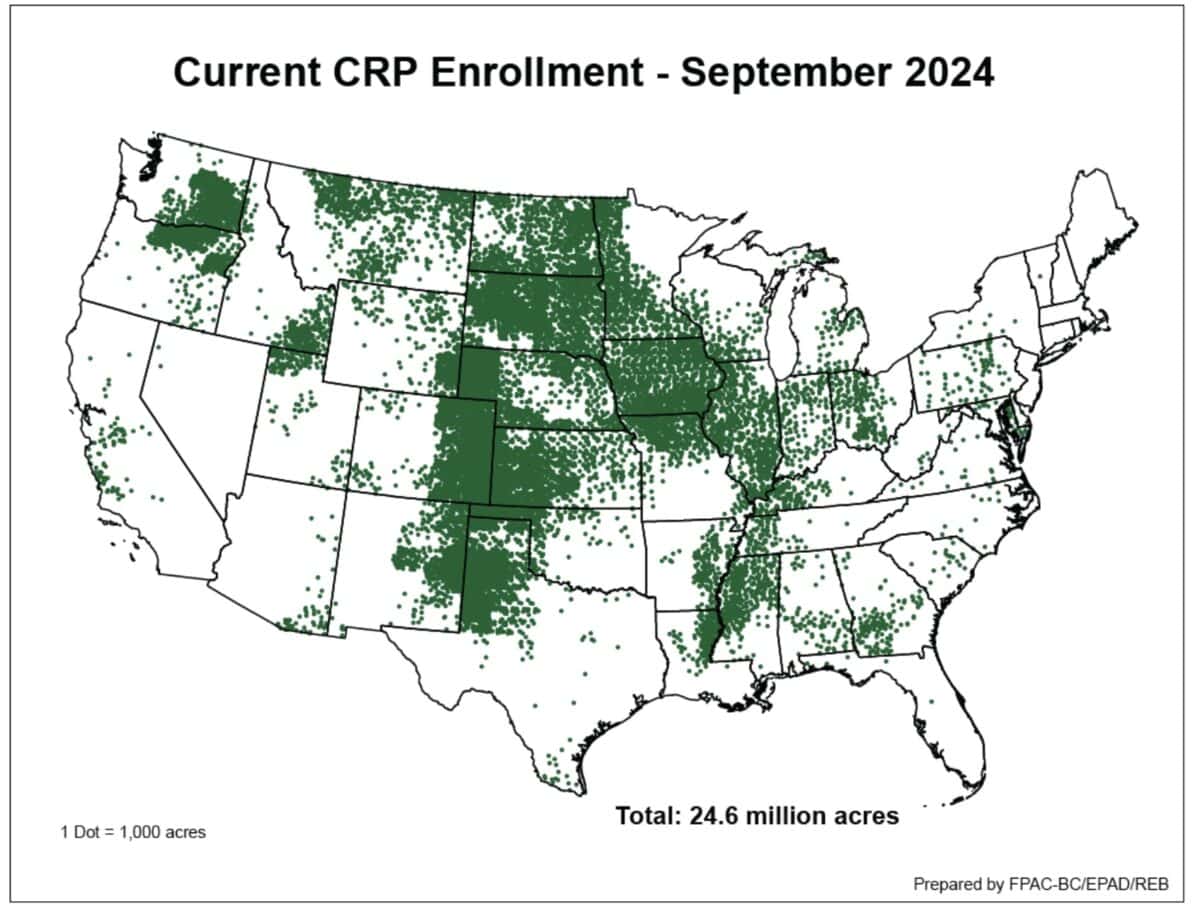

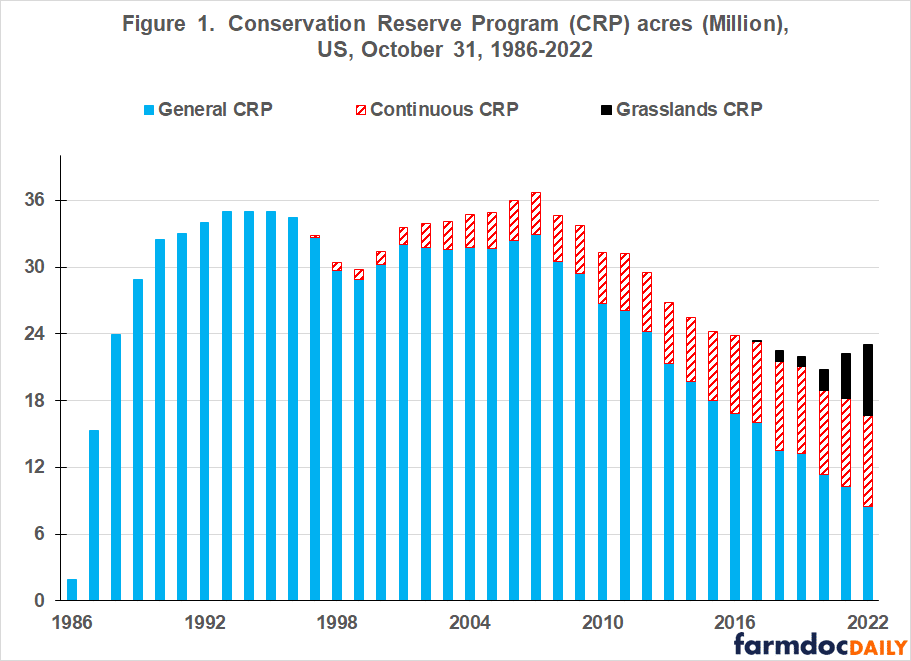

The CRP, created in the 1985 Farm Bill, is a popular program among farmers. Nearly 25 million acres nationwide, totaling nearly $2 billion in payments, are currently enrolled through CRP contracts or through the CRP Transition Incentive Program. Despite years of Republican attempts to cut CRP funding, after more than a decade of decline, participation in the program is now up—thanks to increased funding for CRP in the 2018 Farm Bill. Contracts typically last for 10-15 years, while others are permanent, with goals of improving water quality, preventing soil erosion and preventing loss of wildlife habitat.

The program’s very existence is now threatened. The Heritage Foundation’s Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise—a nearly 1,000-page playbook of guidance and policy proposals for every corner of the federal government that it calls Project 2025—recommends elimination of CRP, along with a host of other farm bill programs.

Project 2025’s Department of Agriculture chapter claims that the CRP is too broad, and that if there is a need for sensitive land to not be farmed, it should be connected to a specific environmental issue. The chapter didn’t offer specifics in relation to reforming or replacing the CRP, just simply a blanket removal.

The chapter was authored by Daren Bakst, the director of the Center for Energy and Environment at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a think tank that advocates for government deregulation. On the Competitive Enterprise Institute website, the think tank takes credit for “convincing President Trump to withdraw from the 2015 Paris climate treaty.”

Bakst did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

The CRP isn’t a perfect program. Some have questioned its ability to generate long lasting, positive impacts on the environment. Critics are concerned that when 10- and 15-year contracts expire, the land is converted back to farmland, reversing any positive impact. “Securing long-term or permanent commitments to convert hard-to-farm land to trees and grasses is the best way to build soil carbon,” says Scott Faber, senior vice president of government affairs at the Environmental Working Group.

Faber says the program should focus more on building soil carbon, which would bring greater environmental benefits. The program currently grants more contracts to preventing soil erosion and to creating wildlife habitat because the tool used to determine who is granted a CRP contract, the Environmental Benefits Index, favors those activities over soil carbon sequestration. “Research suggests that, to store the most carbon in soil, CRP acres should be concentrated in North Central states like Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, Nebraska and Ohio, and land along the Mississippi River,” says Faber.

Project 2025 also claimed the CRP has contributed to rising food costs, particularly as wheat crops in Ukraine have been taken out of production due to the war. However, this claim is not supported by evidence that shows the number of acres of productive farmland in the CRP are at their lowest in decades.

Other challenges have also made the program vulnerable. The expired 2018 Farm Bill means new enrollment in the program has been put on pause. The average payout for participating in the program is about $90 per acre annually, which isn’t a ton of money, but it does add up, especially when the converted land often never yielded fruitful crops. At $90 an acre, Eich believes the low payout likely dissuades some farmers from enrolling in the program. “The financial incentives aren’t necessarily where they need to be to get the program where it is and that it is a couple steps behind necessarily where it should be,” says Eich.

Still, he says, the program’s merits—economic and environmental—are a big reason why it remains popular among farmers. “Being able to provide that permanent habitat for pollinators and the wildlife, that’s really important because we can’t farm vegetables without pollinators.”

Not so with Project 2025. It makes denial of climate change and rejection of climate-friendly proposals a matter of policy. In the document’s foreword, Kevin Roberts, the Heritage Foundation’s president, writes that support for climate-friendly proposals constitutes a form of “environmental extremism” that is “decidedly anti-human.” “It is not a political cause,” Roberts writes, “but a pseudo-religion meant to baptize liberals’ ruthless pursuit of absolute power in the holy water of environmental virtue.”

In keeping with the project’s zeal for deregulation and enthusiasm for fossil fuels, Bakst, in his chapter on the USDA, castigates the Biden administration for including the words “equitable” and “climate smart” in the USDA’s vision statement. Instead, Bakst proposes a new USDA mission statement centered on “personal freedom,” “private property” and “rule of law.”

The foundation claims that Project 2025 is a nonpartisan endeavor, designed as a set of policy recommendations for whichever administration comes next. Meanwhile, Trump has repeatedly denied any association with Project 2025.

Calling the project “nonpartisan,” however, would entail redefining the word, as 182 out of 307 authors, editors and contributors to Project 2025 have strong ties to Trump’s ecosystem of influence. Moreover, Project 2025 makes repeated recommendations to reinstate or extend Trump-era executive orders and proposals.

Trump, in a recent town hall hosted by Univision, responded to a question about potential grocery price hikes if farmworkers are deported, by saying “I’m the best thing that ever happened to farmers.”

During Trump’s first term, the United States imposed higher tariffs on Chinese imports, which led China to retaliate against U.S. exporters. Farm sales to China plummeted and the commodity market was rattled. The Trump administration responded by creating the Market Facilitation Program to bail out farmers hurt by the tariffs, which cost taxpayers $23 billion dollars. The Environmental Working Group found that the top 10% of recipients received 58% of the available funds through the program. The Market Facilitation Program, coupled with bailout money related to the Covid-19 pandemic, resulted in more money being handed out to farmers under Trump than any previous administration.

Under Trump, the USDA also eliminated the Grain Inspection, Packers, and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA), an agency originally designed to protect small farmers and ranchers against meatpacking monopolies. Much like the Market Facilitation program, this Trump administration decision made life harder for smaller farms.

Project 2025, on paper, breaks with the first Trump administration in recommending the reduction of subsidy and insurance programs. However, it’s impossible to predict what would and wouldn’t happen during a potential second Trump administration, as what happens on paper and in practice tend to differ when it comes to Trump.

Chris Eckert, president and CEO of Eckert’s Farm in Belleville, Illinois, about 20 miles outside of St. Louis, says his farm has benefited significantly from apple and peach crop insurance programs. His 600-acre farm became eligible for peach insurance in 1995, which allowed the farm to significantly scale up peach production with less risk involved in the event of a total crop failure. Total crop failures, which were more common when harsh winters were a regular occurrence, are less frequent due to warmer winters. The last time Eckert completely lost a peach crop was 2014.

“The weather that we’re facing today is different than the weather we were facing last year,” says Eckert. “And as a result, we have new diseases, new insects, new issues that arise that we’ve never had to wrap our arms around. So we have to learn our way through that.”

“They’re incredibly important to agriculture in America because the capital requirements to raise food in our country are very high,” Eckert says of crop insurance subsidies. “Most of our profitability is dictated by mother nature, which is totally out of our control, so having some sort of safety net is critically important because we’re expected to take these large financial risks with capital investments of equipment or new orchards or facilities.”

Some of Eckert’s other crops, like blackberries and strawberries, aren’t eligible for crop insurance in Illinois because there isn’t enough of a production history for those crops in the area.

Eckert also says that whoever the incoming administration appoints as Secretary of Agriculture, more so than any Project 2025 recommendation, will have the most direct impact on farmers.

Unlike the leadership of big ag groups like the American Farm Bureau Federation, Eich thinks American agriculture is overly dependent on subsidies, and that subsidy and insurance programs incentivize farms to only produce crops protected by insurance. He says such programs have “historically resulted in the consolidation of farms into fewer, larger, and inflexible farms at the expense of small and diverse family operations.”

Rather than produce a narrow range of crops, Eich produces a large number of crops each year, which is better for the land. If one crop fails, it won’t be a huge loss.

In July, part of Eich’s farmland flooded due to heavy rainfall from Hurricane Beryl, which resulted in some potato crops being submerged in water for over two weeks. “Insurance might have paid off where we did lose some potatoes in the lower ground this year,” says Eich. “But, for the most part we can overcome that through crop diversity.”

Small farmers like Eich face other challenges, such as sourcing equipment. John Deere no longer makes small size tractors that fit his operations, and sourcing parts for much of his vintage farming equipment can prove to be a headache. When he does buy new equipment, it usually comes from abroad, oftentimes Europe or Asia, where small scale farming operations are still common.

Prior to turning to farming full time in 2017, Eich taught elementary school in a disadvantaged community. Serving such communities is still important to him, so he partners with Region Roots, a nonprofit food hub in Northwest Indiana that connects small scale farmers with schools and other community driven organizations.

The direct-to-consumer model has proven fruitful for Eich, particularly at the Chicago-area farmers markets, where he serves freshly popped homegrown popcorn dusted with kimchi powder, which is a big hit.

Eich plans on voting for Kamala Harris. But not everyone in Walkerton, Indiana, is a fan. He says he’s had to replace the Harris-Walz yard sign at the edge of his property multiple times.

.tier-select {

font-family: Arial, sans-serif;

margin-bottom: 1rem;

padding: 0.5rem;

}

Join us to fuel our investigative journalism.

$10

$25

$50

$75

$100

// Function to render the PayPal button with the selected amount

function renderPayPalButton() {

var donationAmount = document.getElementById('donation-amount').value; // Get selected amount

// Clear the existing PayPal button

document.getElementById('paypal-button-container').innerHTML = '';

// Render the PayPal button with the updated amount

paypal.Buttons({

style: {

layout: 'vertical',

color: 'blue',

shape: 'rect',

label: 'donate'

},

createOrder: function(data, actions) {

return actions.order.create({

purchase_units: [{

amount: {

value: donationAmount // Use the dynamically selected donation amount

}

}]

});

},

onApprove: function(data, actions) {

return actions.order.capture().then(function(details) {

alert('Thank you for your donation, ' + details.payer.name.given_name + '!');

});

}

}).render('#paypal-button-container'); // Render PayPal button inside the container

}

// Initial rendering of the PayPal button with the default amount

renderPayPalButton();

This article first appeared on Investigate Midwest and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.