New England’s Forests Are Getting a Climate-Resilient Makeover 🌲

It’s a bold move to keep New England’s beloved woodlands thriving in the face of an unpredictable climate future.

New England’s forests have weathered centuries of change, but climate stress is pushing them to the brink. Invasive pests, creeping diseases, and relentless drought are all taking their toll. But instead of watching the forests struggle, some forestry experts are getting proactive with one of our favorite techniques: assisted migration—planting climate-resilient species that, while not native, are close relatives of local trees. It’s a bold move to keep New England’s beloved woodlands thriving in the face of an unpredictable climate future. A recent study by Clark et. al. (2024) dives into this topic.

Let’s be real: assisted migration isn’t exactly everyone’s cup of forest-friendly tea.

Moving species around is a heated topic in ecology. Experimental trials are still rare, and sometimes downright contentious, especially when trees are getting packed up and shipped long distances. The impetus for this is totally understandable when you realize the damage that exotic trees can cause.

But they are becoming more common. In Canada, Sally Aitken’s team tested Rocky Mountain whitebark pine way up in British Columbia’s colder climes, while Florida torreya trees (which practically have “endangered” in their DNA) were transplanted all the way to Ohio by grassroots activists—raising some eyebrows in the process.

On the home front, U.S. federal agencies are dipping their toes in the migration waters, too. The U.S. Forest Service has launched trials to test whether climate-resilient trees can be relocated to more climate-suitable spots. Even the National Park Service, usually a bastion of "don’t-mess-with-nature" conservation, is cautiously assessing if non-native species can be allowed in protected parklands. Assisted migration, people: where the resilience vs. ecological disruption debate really gets spicy.

More recently, UConn and the University of Rhode Island (URI) have joined forces with the Adaptive Silviculture for Climate Change (ASCC) Network.

Their aim? To experiment with climate-tough species that can keep New England’s tree cover intact as temperatures rise. For southern New England, that means bringing in oaks from nearby states like New Jersey, Maryland, and Pennsylvania—trees that are close relatives of native New England species but have the extra resilience to handle warmer conditions.

If you’re curious to dive deeper, the ASCC Network has a full inventory of trial sites and detailed methodology up on their website, giving forest managers, researchers, and the public a front-row seat to this forward-looking project.

Tackling the Challenges with Data 🛠️

New England’s trials are testing the waters (and the soil) for what actually works in climate adaptation. URI and UConn’s approach organizes test sites into four areas—each with its own distinct mission:

Resistance Areas: The “hold-the-fort” approach—clear out weak trees, let native species regenerate.

Resilience Areas: New England natives get a VIP spot in protective tree tubes to encourage diversity.

Transition Areas: The star of the show—southern oaks and hickories brought in for a climate-resilient backup plan.

Control Sites: Left au naturel as an experimental benchmark.

By comparing outcomes across these test sites, researchers hope to figure out the best practices for forest resilience that’s climate-proof. And these experiments go beyond New England—giving us a sneak peek into how assisted migration could work (or not) globally.

Open Data: Forest Managers Spill the Dirt 📊

Beyond the tree trials, New England forest managers are weighing in with some open-data-powered insights on how to help trees adapt to climate change:

What They Think: Managers are on board with planting regional “cousins” of native trees but are less keen on unrelated species showing up.

Barriers: Shortages of climate-ready seedlings, tight funding, and plain old logistics are standing in the way.

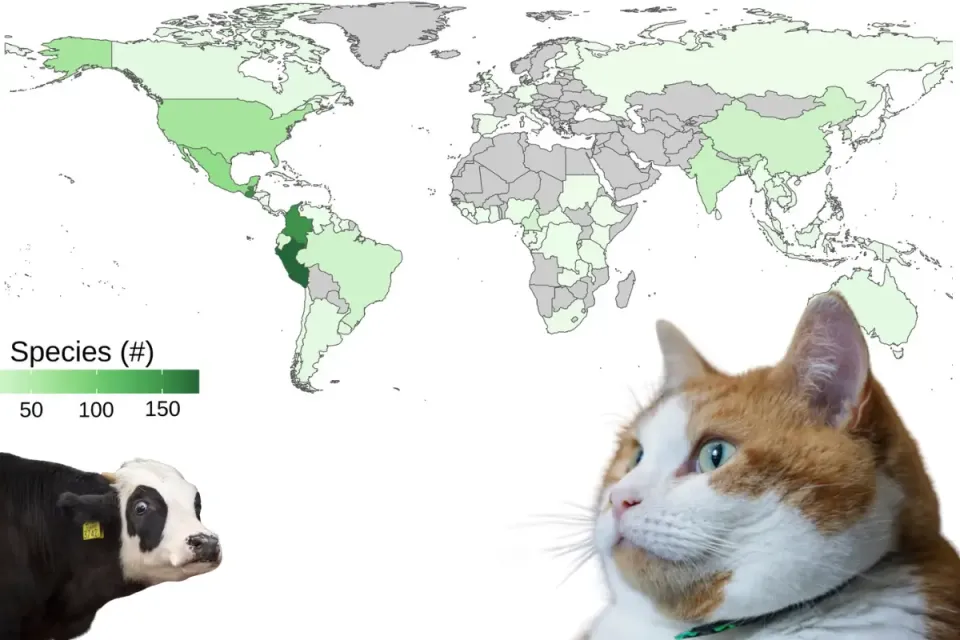

Top Picks: Species like Quercus (oak), Carya (hickory), and Pinus (pine) are topping the list for adaptation trials.

Looking Ahead: A full 93% of managers think assisted migration will ramp up as climate stress gets real.

This data from the Clark study, hosted openly on FigShare, isn’t just for the tree nerds—it’s available for policymakers, land managers, and the eco-curious to dive into, paving the way for a more climate-savvy forest strategy in New England.

In Summary…

From grassroots campaigns planting pines in Canada to nationwide U.S. trials, assisted migration is no longer a fringe idea—it’s becoming a go-to strategy for helping forests weather the climate crisis. And while southern New England’s trees are undoubtedly struggling, don’t count out these tough Yankee forests just yet. As UConn’s Tom Worthley reminds us, New England’s trees have seen worse: after European settlers arrived, they cleared nearly 80 percent of the region’s forests for farms and cattle. Yet, when agriculture waned, the forests roared back. Today, Connecticut alone boasts 75 percent tree cover, with 60 percent of the state wrapped in forest.

“People are spread out among the trees,” Worthley told Sierra Magazine. “We are part of the forest ecosystem.” And if history tells us anything, it’s that New England’s forests—and the people who care for them—know a thing or two about resilience. So, assisted migration or not, it’s safe to say these woods aren’t backing down anytime soon. 🌳

Sources 📚

Forest assisted migration and adaptation plantings in the Northeastern US: perspectives and applications from early adopters. Clark PW, D’Amato AW, Fitts LA, Janowiak MK, Montgomery RA and Palik BJ (2024). Front. For. Glob. Change 7:1386211. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2024.1386211. Retrieved from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/forests-and-global-change/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2024.1386211/full#h7

Ecological Impacts of Exotic Species on Native Seed Dispersal Systems: A Systematic Review. Cordero, S.; Gálvez, F.; Fontúrbel, F.E. Plants 2023, 12, 261. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/12/2/261

Cutfoot Experimental Forest, MN. (n.d.). Adaptive Silviculture for Climate Change. Retrieved from https://www.adaptivesilviculture.org/project-site/cutfoot-experimental-forest

Study restores hope in forest adaptive management 🌳🌱️. Harris, Chris. (2024, October 3). Ground Truth. Retrieved from https://groundtruth.app/study-strikes-another-blow-to-planting-monocultures/

Moving slightly southern trees to New England could help forests survive climate change. Korten, T. (2024, November 10). Sierra Club. Retrieved from https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/moving-slightly-southern-trees-new-england-could-help-forests-survive-climate-change

Can we help our forests prepare for climate change? Ostrander, M. (2018, December 19). Sierra Club. Retrieved from https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/2019-1-january-february/feature/can-we-help-our-forests-prepare-for-climate-change